One of the many things going through my mind during a night of insomnia, are the reflections of Class 2 for this year’s L3 Innovation Challenge. What an exciting night last night! Class 2 included a deeper dive on the Challenge we issued, developing empathy, realizing the power of observation, and doing a crash course on vision science. While science and engineering are often lumped together as STEM, traditionally scientists and engineers didn’t work together. However, convergence has these two disciplines often needing to work together to solve some complex problems, and I wanted both types of students to understand/respect the value of each other in partnership.

Last week, a CITIES Scholar – turned student mentor – turned mentor/guest instructor wrote in his blog writeup “Technology exists in a context defined by its users, environment, and the problem it seeks to solve, — and for true innovation these need to be understood to create true innovation.” This is the heart of STEM innovation, yet I find that it is probably the biggest challenge students in this program every year face. Heck, the impetus for creating the L3 Innovation Challenge was based off of seeing this happen time and time again as a tech/social entrepreneur among colleagues, as a mentor at MIT VMS, and as an angel investor. It’s not hard to see why though…if you’re passionate about something, you want to jump straight into it, and your mind can’t stop thinking about it – from the angle that you are most passionate about. If you think about it, it really makes sense at first glance.

At Class 1, I didn’t reveal this year’s Challenge until the end of class. It was done intentionally because we wanted to prime the students’ thinking first (of course this is a process, and priming in 1 class is not going to change someone’s way of thinking and doing right away). But I didn’t say much, other than the fact that she has had multiple surgeries due to various eye issues, and that she has been categorized as having low-vision. I told them that she’s now 4 years old, and that she’s my adoptive daughter. I didn’t say much beyond that.

At Class 1, I didn’t reveal this year’s Challenge until the end of class. It was done intentionally because we wanted to prime the students’ thinking first (of course this is a process, and priming in 1 class is not going to change someone’s way of thinking and doing right away). But I didn’t say much, other than the fact that she has had multiple surgeries due to various eye issues, and that she has been categorized as having low-vision. I told them that she’s now 4 years old, and that she’s my adoptive daughter. I didn’t say much beyond that.

More than any other year, I was excited to have students share with me that they’ve already been thinking about my daughter after last week, and have already designed some ideas of how to help her. My heart fluttered, because of course anyone who spends their spare time thinking about ways to help my daughter without being asked to (I didn’t assign any homework last week), I find really touching because they were really passionate about finding ways to help her.

However, it was only in Class 2 that I shared more about my daughter’s condition. I switched hats and went from Founder of Youth CITIES to “Mom, key stakeholder”. I talked about how we adopted her a little over a year ago when she was 3 years old. I talked about what our family life was like, and how she told me last October – when she had only been in the States and with us as a family for about 3 months – that she wanted to be out on the ballfield playing baseball when we were at Fenway Park, watching the World Series. Ok, I got it…you don’t want to just be a spectator of the sport…you want to play the sport. Many students often re-take my classes, and several students this year remembered how I missed a class last year because my daughter had multiple procedures done earlier that day, and I was at home with her while she recovered.

However, it was only in Class 2 that I shared more about my daughter’s condition. I switched hats and went from Founder of Youth CITIES to “Mom, key stakeholder”. I talked about how we adopted her a little over a year ago when she was 3 years old. I talked about what our family life was like, and how she told me last October – when she had only been in the States and with us as a family for about 3 months – that she wanted to be out on the ballfield playing baseball when we were at Fenway Park, watching the World Series. Ok, I got it…you don’t want to just be a spectator of the sport…you want to play the sport. Many students often re-take my classes, and several students this year remembered how I missed a class last year because my daughter had multiple procedures done earlier that day, and I was at home with her while she recovered.

I shared lots of photos, including the ones below, and videos. The students observed how she looked at things, they learned what types of activities she likes to do (including playing/watching baseball, learning to skate because she wants to play hockey, etc), her various learning environments (she’s in Pre-K every day, goes to Chinese school once a week, has music lessons, etc), and has to navigate through life – literally and figuratively. I was impressed and honored at how attentive the students were, how many questions they asked, and how many notes they took.

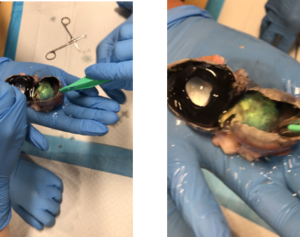

As Liz Kong (PhD in Genetics, my partner-in-crime for creating some of the different pieces of curriculum around the changing annual challenges for this program, and “Auntie” to my 3 kids…especially to my daughter because of her scientific knowledge – and support as my dear friend – during the adoption process), went more into detail about my daughter’s condition, we had a  crash course on vision science. As a mom and having to learn so much about how vision is supposed to work, and how my daughter’s vision “works” over the past year has been pretty intense. Her rare genetic mutation does what? What’s wrinkled and what’s pinched? You mean she sees the world like what?!? What I love about Liz is how she goes about explaining very complex issues in ways that even a layman can understand…and certainly the disgustingly cool part of examining the parts of a real eye (instead of looking at screen depictions of my daughter’s scans) finally helped me understand my daughter’s condition better. But, oh wait, we’re doing this for the students…right, so in addition to helping me understand my own daughter’s condition better, we were able to create a very memorable learning experience for the students (many manipulated the eyes, many, like I, just chose to observe and not touch). But regardless of how close we got to the actual eyeballs, we all got a better sense of what’s going on “behind-the-scenes” with my daughter’s eyes.

crash course on vision science. As a mom and having to learn so much about how vision is supposed to work, and how my daughter’s vision “works” over the past year has been pretty intense. Her rare genetic mutation does what? What’s wrinkled and what’s pinched? You mean she sees the world like what?!? What I love about Liz is how she goes about explaining very complex issues in ways that even a layman can understand…and certainly the disgustingly cool part of examining the parts of a real eye (instead of looking at screen depictions of my daughter’s scans) finally helped me understand my daughter’s condition better. But, oh wait, we’re doing this for the students…right, so in addition to helping me understand my own daughter’s condition better, we were able to create a very memorable learning experience for the students (many manipulated the eyes, many, like I, just chose to observe and not touch). But regardless of how close we got to the actual eyeballs, we all got a better sense of what’s going on “behind-the-scenes” with my daughter’s eyes.

Now is the point where we circle back to designing a solution for my daughter. Some students are really examining the various scenarios that she has to go through on a daily basis, and with her favorite activities. Others still love to talk about the various “solutions” they have conjured up to help her out. Every year, while I see this process unfold with the students, I also observe how our amazingly skilled and experienced mentors and guest instructors react when some students still get really excited about the various inventions, mock-ups, even renderings, that they’ve already created. Yes, the design-thinking process might come more naturally to some people than others…but I don’t necessarily see it as a strictly linear process. These STEM-inclined students are already creating amazing pieces of technology; admission into this program is application-based…many of these students have won science fairs and robotics competitions.

Yes, true tech innovation needs to incorporate the “human side of STEM”, understanding that innovation only works if it has been thoughtfully designed in the context of its users and its environment and other narratives around it. However, we all get our spark differently, and that’s ok. Some people are drawn to a particular problem to solve, and others are drawn to the opportunity to tinker and build something new. If you had an assignment to write a story and create a picture that goes along with it, should you start with the story-writing so you’ll know what type of picture to create with it? Or do you conjure up a picture (whether realistic or abstract), and then create a story that is inspired by the artwork? One may cause a brain cramp if you force it to be your starting point, while the other may be the springboard for inspiration…and both of those may change, as first drafts are rarely the final drafts. You may realize afterwards that the assignment required the use of a particular medium that you didn’t use at first…or that your story was required to incorporate a historical figure. Wearing a baseball cap. Discovering the joys of eating a mango. But there’s a word limit to your story. That you’ve already surpassed. And you just realized that your story is supposed to be written for a different audience than you had in mind. So, you research. You ponder. You tweak. And you revise. And you refine. A little more to your story. A little less to your visual. Whatever it may be, it’s a work in progress. Until you get it just right. Where it feels true to the creator, and meets the teacher’s requirements. Andrew summed up my beliefs nicely in last week’s blog: “The spark of inspiration for a solution can be driven by the prospect of initial technology, or by the identification of a problem that needs an innovative solution. Both are valid places to start, but require the other to completely flesh out an innovation that both fulfills a need and is technically feasible.” I don’t believe we need to snuff out the initial spark in order to satisfy a process. Rather, I view it more like a puzzle. You can start along the edges, or you can find an object in the middle of the puzzle to start with…but at the end of the day, you need the border and everything in the middle for the puzzle to be complete.

I smile when I see mentors say “a lot of the students are jumping straight into the tech solution!” Yes, they need to incorporate the needs of the user, take into consideration the user’s habits, and the stakeholders/environment that creates the narrative around the problem…this crazy thing called real- life. And even more importantly, the user’s real-life, not the designer’s real-life…because the realities of your life and my life could be drastically different. I smile because this is why I created the L3 Innovation Challenge. Precisely because, more often than not, the natural tendency is to build and create based on our own assumptions. If in Class 1 or Class 2 the students already understand that technical innovation shouldn’t be created in a silo, then this program would still be really cool, but more of a nice-to-have, not a need-to-have. But the truth is, I’ve seen way too many adults jump straight into creating “products”, only to have it either tossed aside immediately by the user…or have a great product that doesn’t get long-term traction because it didn’t groove with the natural habits of the intended user. But can the technological innovation be matched with the needs of the user? That, is the biggest challenge. But understanding that is what will transform a Science Fair kid or Hacker into a true STEM innovator.